Power and Persuasion in the 'Theatre' of Camillo

Polish and English Art Historian's Publication

Kate Robinson 2003

NB. For Bibliography and notes, see publication

For Giulio Camillo Delminio (?1480-1544), power and persuasion was in the domain of the spoken, rather than the written, word. A natural philosopher, an orator, a European gad-about, in his time, Camillo was a celebrated man. The King of France, no less, was Camillo's patron; he had a close working relationship with the painter, Titian; he was at the centre of a vitriolic row with Erasmus that was to rock Europe. Like Erasmus, Camillo was aware of what has been called the 'metaphorical force' of language, a force that is able to give language a 'turn' , and the necessity of using it judiciously. There was about an orator the mystique of a magus. The breath of his word effected miracles. It could move the woods.

Posthumously, Giulio Camillo's memory was kept alive by a number of scholars during the sixteenth century, including Ariosto, who said that Camillo showed 'a smoother way to the heights of Helicon' (Orlando furioso, XLVI, 12). Historians such as Frances Yates The Art of Memory (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1966) and Lina Bolzoni Il teatro della memoria: studi su G. Camillo (Padua: Liviana, 1984) subsequently revived his reputation. And, recently, he has inspired contemporary artists from a variety of disciplines, including the composer, John Fuller The Theatre of Memory (Proms, London, 1981); the video artist Bill Viola The Theatre of Memory (video installation, California, 1985) and the writer, Umberto Eco L'Espresso (14th August 1988). As a sculptor, my first response to Camillo's work resulted in an exhibition, The Theatre of Memory (Collins Gallery, Glasgow, 2001), images from which are reproduced in this paper. A brief web-surf will reflect the current burgeoning response to his work.

Camillo was certainly not without his detractors, however. Even his earliest promoter was equivocal: Lodovico Domenichi, in his dedicatory letter to Don Diego Hurtado, of the first edition of Camillo's L'idea del Theatro (Florence: Torentino, 1550), published posthumously, implied that his reputation may have suffered because he had 'promised too much'. Tiraboschi, writing in 1824, said that the Theatre was a 'vain and incredible thing'. Within the last fifty years, he has variously been called 'one of the most famous men of the sixteenth century' , the 'peak of absurdity' , 'an amusing…impostor' , and the 'great actor of the Renaissance'.

To what does Camillo owe his fame? A recent compilation of Camillo's work (L'idea del Theatro e altri scritti di retorica (Turin: Edizioni RES, 1990)) show the scope of his interests. He was intrigued by language, charting regional differentiations in the Friulian dialect, in the area near where he was born. He enjoyed word games, coining a phrase - gorgo dell'artificio, or the 'whirlpool of artifice' - for the centre of a visual device that married literary opposites. In the centre of the whirlpool there was space for the hidden and uncontrollable, a space for language, for the sign, to disintegrate and re-form. He thought that here opposites could be reconciled, material changed, transmutation made possible. And his curiosity also extended to matters scientific. In L'idea dell'eloquenza, for example, written circa 1530, he discusses the nature and order of the planets, the work having has a strong alchemical theme. Broadly speaking, it could be said that Camillo was a natural philosopher in the same tradition as other northern Italian thinkers, such as, for example, Pietro d'Abano (ca. 1310), and Giovanni Pontano (1426-1503). He fuses a vision that is rooted in the body of man with a conception of the planets and stars, with the influence of the 'heavenly streams' that animate the universe with the atomic structure of the world. However, there are two aspects of Camillo's worldview, expressed in his final work: L'idea del Theatro, on which this paper is focussed, that particularly mark him out. Firstly: his reliance on the visual sign as a conveyor of meaning. Secondly: the heliocentrism that is implicit in his metaphysical picture.

Little, if anything, of Camillo's work was published in his lifetime. L'idea del Theatro was not initially conceived as either a public - or a published - work at all; it was private, a secret between Camillo and the King of France, as I later discuss. L'idea del Theatro instead reflects Camillo's memorised system: it is the work of a speaker, not a writer. Camillo understood that there was an important relationship between the image and memory, giving a glimpse into the orator, or preacher's, methods of re-call. Within an image a pattern of knowledge could be stored and later retrieved, as it could impress upon the mind's eye an impression so visceral and emotionally significant that it had the equivalence of a vast data bank. Like a seal in wax, like a signature, images gave access to immediate, instinctive recognition and remembrance. In L'idea del Theatro, Camillo describes the universe in highly visual and mythical terms, although there is not a single drawing or diagram in the book. The world, the planets and history are pictured as a vast network of visual relationships. This imaginary network is arranged within the context of a celestial Theatre, in which everything from the rocks and stones to the very hairs of our head is sentient and receptive of celestial energy.

Venus at the Level of the Cave, Kate Robinson 2001

Biographical details of the early life of Camillo are sparse, and his biographers contradictory. He was born in Friuli, in either Portogruaro or in Udine, in the north east of Italy, in around 1480. The region of Friuli, between the Alps and the Adriatic, Slovenia, and the Veneto, had been an important strategic centre since Roman times. From the 6th century it had been home to the Christian Patriarch of Aquileia, in constant conflict with Rome. In the early fifteenth century, after its defeat by the powerful Republic of Venice, it was famous for its mercury mines, its witches and its alchemy. Around the time of Camillo's birth it was in the throes of one of the earliest of the Peasant Revolts that were to ripple throughout the continent.

Camillo took his family name, Delminio, from the birthplace of his father, in Dalmatia, in what is now Croatia, and his life was spent in Italy, France and Switzerland. He studied philosophy and jurisprudence at the University of Padua and is believed to have held a chair of Dialectics at the University of Bologna from around 1521 to 1525, and is known to have been one of the 'court of intellectuals' at the Coronation of Charles V in 1529. Camillo was in Venice around the first decade of the sixteenth century, and lived near the house of the famous printer, Aldus Manutius. This was in the Sestière di San Polo, where Camillo was part of a close circle of writers, scholars and artists. He was a friend of the architect, Serlio, whose influential Libro d'Architettura (Paris, 1545) was later to have a profound effect on theatre design. Camillo's friendship with Venetian painter, Titian, resulted in an illustrated copy of L'idea del Theatro, which, sadly, did not survive a fire at the Escorial in 1671. Camillo was also an associate of the writer Erasmus who lived in Italy between 1506-9, in Venice and Rome. Erasmus was later to write Ciceronianus (Paris, 1528), in which the name of Camillo plays a pivotal role. Ciceronianus scandalized Europe, and may have been instrumental in prompting Camillo's journey to Paris in 1530.

Camillo travelled to Paris in company with his agent, Girolamo Muzio. This was in an attempt to raise funds from the King of France for the great work on which Camillo devoted most of his energy: his Theatre. We do not know what passed between the King and Camillo, but whatever Camillo's 'pitch', he so impressed François 1st that he was given generous funds to develop his ideas on condition that he should not divulge his ideas to anyone else: the Theatre was to be François's secret. Camillo remained true to this stipulation right up until the months before he died.

While in Paris, Camillo wrote a reply to Erasmus's attack: L'idea dell'Imitazione that circulated the capital in manuscript. He also worked on some kind of model of the 'Theatre'. Camillo was not talking about a 'Theatre', in the sense that we now use the word, and it is difficult to tell whether the model would have had an architectural nature, or whether it resembled a kind of library , or a gallery of images , or an astronomical orrery, with sculptures of the planets. But however Camillo spent his time, he seems to have made an impression in Paris. It appears that he was a man of some physical presence and there is a story that one day, 'in a room with many gentlemen at some windows looking out over a garden,' Camillo was confronted with a lion that had escaped from its cage. 'Drawing near to him from behind, with its paws, [the lion] took [Camillo] without harm by the thighs, and with its tongue, proceeded to lick him.' '…That touch and…that breath, himself being overturned…all the others having fled' appears to have had a profound effect on Camillo, and images of lions appear often in his writings. The lion story was corroborated by a number of sources and cannot have harmed Camillo's mystique.

Eventually, though, remuneration from François began to dry up and around 1537 Camillo decided to return to Italy for good. Little is known of him during this period, though the Theatre must still have been an important feature in Camillo's life. During the latter part of 1543, or very early in 1544, he accepted an offer brokered by Girolamo Muzio, to go to Milan. Here, in Milan, at the court of the Marchese del Vasto, after much persuasion, Camillo finally told Muzio the details of the Theatre, which François had sworn into secrecy. Muzio transcribed all that Camillo said, over the course of seven days and nights. An apocryphal tale has it that Camillo and Muzio reclined on two adjoining beds while Camillo held forth, in emulation of ancient philosophers. The manuscript was completed early in February 1544. Three months later, on the 15th of May, Camillo died.

However, Muzio and the Marchese del Vasto decided not to publish Camillo's manuscript, and L'idea languished. These were turbulent times and there may have been many reasons for their hesitation, but it was not until six years later that L'idea received a wider public, when the manuscript turned up in the hands of Antonio Cheluzzi da Colle. Da Colle put the manuscript in order, and L'Idea del Theatro was finally published in Florence in 1550. So, what was in L'Idea del Theatro to delay its publication, though such lengths had been taken to attain the manuscript? One reason for the delay, as I discuss, may have been that codified within Camillo's scheme, though never explicitly stated, is a picture of the universe with the sun, rather than the earth, at the centre.

Pyramid at the level of Mercury, Kate Robinson, 2001

Camillo is imagining a 'theatre' in its original sense - as a place in which a spectacle unfolds. Written in Italian, L'idea del Theatro is arranged in seven sections that chart the creation of the world and 'the eternal nature of all things'. He says:

Following the order of the creation of the world, we shall place on the first levels the more natural things…those we can imagine to have been created before all other things by divine decree. Then we shall arrange from level to level those that followed after, in such a way that in the seventh, that is, the last and highest level shall sit all the arts… not by reason of unworthiness, but by reason of chronology, since these were the last to have been found by men.

L'idea del Theatro, pp.10-11.

Camillo believed that by reducing knowledge to its constituent parts, you could come closer to comprehending its original essence, and consequently understand what makes the universe tick. Likewise (but in the opposite direction) through comprehending the universe, you would understand its essential ingredients. His key to this was in the creation of a symbolic system that both represented the essence of material, as well as the relationships between the essences that allowed the universe to maintain its being. The 'idea of the Theatre' was fundamentally a structure of conceptual relationships rather than a building of wood or stone, and it is on that level that Camillo's work bears most fruit. The Theatre is to be understood in terms of time and space - a spatial representation of chronology - a clock of epochs.

Camillo speaks of a system that, as he says, makes 'scholars into spectators'. He says:

The oldest and wisest writers always have had the habit of protecting in their writings the secrets of God with dark veils, so that they are understood only by those, who (as Christ says) 'have ears to hear', that is, those who are chosen by God to understand His most holy mysteries. He continues by saying that Moses, after returning from the mountain and his encounter with God, 'could not be looked upon by the people, unless he covered his face with a veil'.

Ibid. p.7

And then, later, that the Apostles were only able to comprehend Christ through 'signs and visions'. For Camillo signs, by definition, were riddles, sphinx-like and sacred, to be understood only by lifting aside the veils, which conceal them.

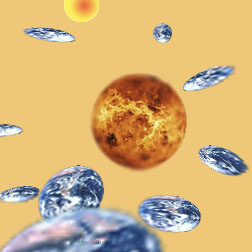

The entire Theatre, says Camillo, rests on Solomon's Seven Pillars of Wisdom, out with which number 'nothing else can be imagined'. On the Seven Pillars rest the planets, which govern, or administrate, 'cause and effect'. Camillo names these planets: the Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Significantly, Camillo omits the name of the Earth. Arranged in an ascending order from the planets, and affected by their influence, are a further six levels, which, broadly speaking, represent a gradual development from nature to art. They are named The Banquet, The Cave, The Gorgons, Pasiphae, The Sandals of Mercury ('I Talari'), and Prometheus. The Banquet and the Cave, are the most 'elemental' of the levels. These are the levels where creation first began. After these, come the levels of the Gorgons, and Pasiphae, where the 'inner' man is revealed in relation to the cosmos; these levels are part nature, part art. And then there are the levels of the Sandals of Mercury and Prometheus, which are concerned specifically with man as an active agent within the world, or art and man. There is an inversion at the central part of the second and first levels between 'The Banquet' and 'The Sun', represented by 'Apollo', and Camillo makes it explicit that The Banquet and the Sun, here, are very important positions within the whole plan. I will return to this aspect later.

Camillo describes 'doorways' placed on each of the levels beneath which the scholar, or spectator, may view images to represent, and to remember, salient features of that position within the arrangement. There are over two hundred of these 'word images', or visual metaphors, taking up about a third of the text of L'idea del Theatro. The initial naming of the levels in effect creates a kind of grid system. The underlying grid system affects the interpretation of a given symbol or image; certain images, for instance, are repeated, however, their interpretation, or meaning, is altered, by their position within the grid. Rather than a graph based on numeric values, the values in Camillo's scheme are based on language and myth.

Girl with her hair raised to the heavens, Kate Robinson, 2001

Many of the references of the imagery within the Theatre are now obscure, though they all possess resonance. To take just one example, "The Young Girl with hair raised toward the Heavens" is meant to symbolise 'a vigorous thing either strong or trustworthy'. Camillo explains that the image is based on Plato's idea of man being a tree upside down 'since the tree has its roots below and man has his above'. He goes on, citing Origen and Jerome, to explain that the hair should be understood metaphorically as representing a part of the soul, just as the 'beard, eyes, and other parts corresponding to the body' should be interpreted, Biblically speaking, as correspondent to an aspect of what he calls the 'interior man'. In this way, just as 'the tree draws to itself through its roots the nutritive moisture from the earth, so the beard and hair of our interior man should draw dew, that is, the living moisture from the influxes of the celestial channels, from whence comes all its strength.'

Camillo is envisaging a vital equivalence between the body present in time and space and the eternal, between every particle of the body and the cosmos. This is operated through a correspondence on a sensual level with the 'inner man'. In the hair and beard and eyes, there is a tangible, personal, corporeal contact with the cosmic strength imparted through the 'celestial channels'. Bodily parts are connected to heavenly attributes. Elsewhere he says that just '…as the stars are the eyes of this world, so the plants and trees…[are] the skin and hair of its body and the metals and rocks are in the same way its bones…'. And later, he says 'the world lives'. Vegetative matter, minerals, rocks, the cosmos and mankind all are in a state of constant reception of the 'water of wholesome wisdom'. Camillo constantly reiterates his motif of an animate world in which every element is sentient of, and responsive to, its source.

Following in the footsteps of the Dominican scholar, Marsilio Ficino (1433-99), Camillo believed that the sun, which 'fosters and nourishes all things…is the universal generator and mover'. And, though not explicitly acknowledged by Camillo, L'idea owes much to the writings of Pico della Mirandola and Lorenzo Valla. In common with other philosophical/scientific authors of the period, Camillo backs up his theories by referring to Biblical and Classical sources, notably Lucretius's De Rerum Natura. More unusually, the whole work is also liberally peppered with references to Cabbalistic writings; Camillo, living in cosmopolitan Venice, clearly enjoyed intellectual commerce with his Jewish neighbours. Like Ficino, Camillo is usually perceived as a literary scholar and he has most often been judged in relation to those who deal in words. But Camillo's aim, his universal picture, is one that intimately combines the principles of natural philosophy, astronomy and number with mythology and language in a way that is markedly more systematic, or 'scientific', than Ficino.

While the language that Camillo uses is based on art and mythology, his thinking is rooted in scientific principles that bear direct correlation to other Renaissance astronomical theories of the day. Useful comparisons can be made between Camillo's L'idea and astronomical treatises such as the celebrated Sphera of Sacro Bosco (composed during the thirteenth century and used up till the seventeenth), Pontano's De Rebus Coelestibus (Venice, 1519) and the great Polish astronomer Copernicus's De Revolutionibus, which had been published in Nuremberg in 1543, a matter of months before Camillo dictated L'idea to Muzio. It is significant that both Camillo and Copernicus worked or studied at the Universities of Bologna and at Padua, a greenhouse for new astronomical ideas. Even if they were not personally acquainted, they would have been aware of a common parlance. On a broad level, there are correspondences in terms of some of Copernicus's and Camillo's influences, the Pythagoreans and Trismegistus, for example. They also share a reluctance to make their findings public. However there are also conspicuous divergences. The flavour of Cabbala, for instance, in L'idea del Theatro, is not apparent in De Revolutionibus. L'idea is couched in mystical terminology, in visual image and metaphor. This is not to say that the material, scientific conclusions to which Camillo is drawn in terms of planetary arrangement and movement, should be underestimated. Camillo utilizes contemporary philosophical tools: his conclusions evolve from a working combination of philosophy and contemporary theories of astronomy. It was not unusual for natural philosophers to disregard the efficacy of mathematical methodology. Wojciech of Brudzewo, for example, who taught from 1474 until his death in 1495 at the University of Cracow, and is thought to have been Copernicus's mentor in astronomy, "explicitly divorces natural philosophy from mathematical astronomy". Real phenomena, for Camillo, belong in the realm of natural philosophy, while the imaginary, or hypothetical, belong in the area of mathematics.

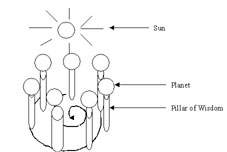

For Camillo, a natural philosopher rather than a mathematician, to address astronomy was not in itself unusual. What was extraordinary was that he attempted to do this by tackling the issue - in a literal sense - spatially. And, from a spatial perspective, Camillo envisaged a fundamental departure from illustrative models of planetary arrangement that had existed in the past. The idea for Camillo's 'Theatre', attempts to locate in a tangible space (and in 'real time', to use a current visual art term) the heavenly and terrestrial relationships. Shown below, is a very simplified diagram of the layout of the interior part of Camillo's Theatre, the level of the planets, and a part of the second level where the sun is located. The diagram does not represent any of the imagery within the Theatre.

Interpretation of inner part of Camillo's Theatre, Kate Robinson, 2003

In L'idea del Theatro, Camillo says that the sun has 'the most noble place of all the theatre'. The sun is in the fourth place in the second level of the Theatre, that is, at the level of the Banquet. The Banquet is the place where the very 'productions [of] God' originate. 'In this place,' says Camillo, 'ordinarily devoted to the Banquet, Apollo shall be placed…[and]…the sun itself shall be discussed'. The first level, where the planets are positioned, is described by Camillo in terms that mostly reflect the Ptolemaic order of the planets, which had been accepted for centuries by astronomers as correct. He begins with the Moon; then Mercury and Venus. At the fourth place, however, instead of a planet, he places four of his descriptive images, discussed further below. From the fifth to the seventh position on this first level, he again reverts to placing images of the planets: respectively, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.

The four images at the central position on the first level, mentioned above are are: the 'Breadth of Being'; the Fates; the 'Golden Bough'; and Pan. Camillo says that the 'Breadth' or 'Magnitude of Being' is represented by the shape of a pyramid, which symbolizes the 'Divinity, unrelated and in relationship'; the appearance of the Fates symbolise cause and effect; the tree, or 'Golden Bough', stands both for 'intelligible things' as well as 'those we can only imagine…enlightened by the Active Intellect'. Pan represents the three levels of the world. Camillo says that in the representation of Pan:

….his head symbolizes the supercelestial [world], with his horns of gold which point upward, and with his beard, the celestial influences, and with his starry hide, the celestial world, and with his goat legs, the inferior world.

Ibid. p.15

The images of Pan, the Golden Bough, the Fates and the Breadth of Being, are placed in the position where, in the Ptolemaic order, it would have been usual to place the sun. But, as mentioned above, the sun is relocated to the level of the Banquet - the single planetary sphere to be so positioned. The Earth, the ground on which this pantheon of images is witnessed, on the other hand, is neither explicitly named nor placed by Camillo. Is this omission accidental? He goes to great lengths to explain that due to the magnificence and power of the sun it has been given its own noble location, and discusses the elemental, mythic and angelic attributes of each one of the other six planets. It seems unlikely that he would have forgotten to mention the earth, in this context. As he states in the opening pages of L'idea, the very planets themselves are the original starting point for the whole Theatre, each of them resting on one of Solomon's Seven Pillars of Wisdom. The position of the Earth, however, never explicitly discussed in L'idea, is left to be inferred. Though the Earth is not mentioned, could it be that we are to understand its glyph in the four images named above: Pan, the Golden Bough, the Fates and the Pyramid? Each one of these images powerfully connects the mundane and spiritual, the planetary and heavenly.

It is significant that four images are represented at this point. The number four, according to mediaeval geometry, was associated with stability and, geometrically speaking, the four-cornered square was meant to represent the earth. The figure of Pan described by Camillo unites the three levels of the world: the supercelestial, the celestial and the inferior. With his goat legs resting on the inferior world, the body of Pan reaches up and connects all the other levels. This is a cosmically proportioned representation of Camillo's 'inner man', working at the level of the stars, yet positioned on the earth. It is significant that Pan himself should be described in terms of four elements: his head and golden horns symbolizing the supercelestial world, his beard, the celestial influences, or 'streams', his starry hide, the celestial world, and his goat legs, the inferior world.

It is also interesting that the Fates should be positioned here. The Fates, according to Camillo, signify 'cause and effect'. At the beginning of L'idea Camillo states that the Theatre is the place where first causes leading to their consequent effects will be discovered. From an astrological point of view, the earth, and more precisely man on the earth, is where the influence of the other planets will be experienced, the earth is the epicentre of astrological determinism. However in Camillo's model, causes and effects stem from the earth, rather than the other way around. The relationship of the earth to the other planets is active rather than passive. Is Camillo, then, suggesting that his new planetary model bypasses astrological influence? Is he saying that, in his model, the earth itself, or man on the earth, has autonomous power over cause and effect? The relationships within the Theatre in terms of planetary influence are based on the assumption that particular planets have certain innate characteristics that can change aspects of existence, e.g. Saturn and the Moon have effects on time, Mercury has influence in communication. Yet as Camillo has switched the traditional positions of the sun and the earth, and, what is more, suggested that first causes come from the earth itself, the affect of the other planets is no longer controlling. Instead, all of the planets are part of an equal, changing, transformative organism. I think that this aspect of Camillo's Theatre was at least as radical as suggesting that the sun was at the centre of the universe. As late as the seventeenth century, judicial astrology, for example, was still seriously considered, and yet Camillo was suggesting a new model based on autonomous self-sufficiency.

Spheres at the level of the Banquet, Kate Robinson, 2001

Camillo's message, whispered in the ear of the King of France, was about power. Harnessing spiritual, temporal and personal power was precisely what Camillo cared about and travelled Europe to advocate. Camillo shows us what matters to him in L'idea del Theatro when he talks about the ability to predict the time of one's death, or a spiral of love setting everything in the universe in motion, or the transformation of spirit and matter. Illusion, appearance, dissimulation, signs, visions and eternity are what interest Camillo, as well as the skill, Prospero-like, to interpret and orchestrate the symbols and attributes of the world. For along with preaching the power of transformation, Camillo also talked about practical steps of how it could be achieved. And this itself was based on Camillo's understanding of the central position of the sun in the universe.